| Voicing the Deepest Desire: an Interview with Joanna Macy and Louise Dunlap, August 2010 in Berkeley, California

|

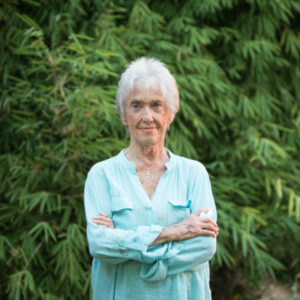

| Louise Dunlap “sat” this active seven day retreat. One afternoon, bringing a bright moment of levity, she shared a poem she wrote that celebrates the frogs we hear on spring retreats at Spirit Rock: “rrk, veep! rrk veep!”Louise, a writing teacher and veteran of the Free Speech Movement, wrote Undoing the Silence, a book packed with exercises to help free and hone the words of those writing for social change. |  |

| Joanna is a renowned Buddhist ecologist, thinker, and teacher. She is the author of several books including World as Lover, World as Self. Grounded in Buddhist teachings, her writing and workshops help people consciously experience their pain and compassion for the world. |  |

| Both women are peace activists, environmentalists, Buddhist practitioners, and mostly, master facilitators who help move people from overwhelm and into action and self acceptance. They have known each other for a few years, but have only recently become closer friends. The interview took place in Joanna’s Berkeley home. | |

| K: How did you first come to be involved in social change work? Can you describe the first time you engaged in political action and what that was like for you?

J: It predates my learning about Buddhism. It was through Christianity. I was very influenced by the social gospel, the teachings of justice and compassion and courage for speaking truth to power that I was exposed to in liberal protestant Christianity. I was very blessed with wonderful pastoral teachers, and the student Christian movement, which is how I met my husband. K: Do you remember the first meeting or gathering or protest? J:You know I can’t. It goes back so far. I tell in my memoir, Widening Circles, how at sixteen I was at a conference learning from an air force chaplain – it was right after the war -who talked about how we were crucifying Jesus by the war profiteering, the exploitation of migrant labors and the migrant labor camps -just case after case! So if you have an appetite for the sacredness of life, feel yourself part of a larger spirituality, which to me is the essence of spirituality, then it immediately implies service, and service to the dignity and beauty that’s inherent in all life forms.So my social activism has very strong Christian roots and also Jewish roots because the Hebrew prophets were very thrilling for me-they didn’t mince words! L: My first memory of being an activist was kind of a setup. My father’s uncle was a legislator in Sacramento. When I was in junior high, my mother and he arranged for me to travel up there by train to give testimony at a committee hearing about whether they should they build a highway through the redwoods. I went and stood up in front of the senators and said that I didn’t think they should cut down any more redwood trees, they were the most beautiful thing in the world, and we should preserve them! Isn’t that cute? I didn’t really start to question the status quo until I was in graduate school at Berkeley in the early sixties during the Free Speech Movement. You had to take sides in that and I immediately realized that the activists were right. That we should be allowed to hear speakers on all subjects and we should be allowed to make up our own minds, and the university shouldn’t shut down student tables or have anything to say about what we thought or said. That was my first radicalization.I handed out leaflets and I carried picket signs, which had always been anathema in my family. My parents were Republican at the time, and they lived right here in Berkeley. “You’re listening to too many pinkos, miss,” my father would say. J: I was fascinated by how the Buddha built a sangha that had no private property, that made decisions by consensus, that modeled social inclusiveness and resisted the caste system, etc.I’ve often suspected that I was importing my Christian derived social conscience into Buddhism, but then I was glad to see that it was there from the beginning very, very strongly. The social revolutionary nature of the Buddhist teachings have been not as clearly brought out for many Buddhists because western Buddhists tend to go for personal tranquility and escape. Paticca samuppada -dependent co-arising -is all about how we belong to each other.And after meeting the Tibetans and meeting Buddhism in the flesh in India, I had a kind of mini satori experience of getting it about no-self. My instant response to no-self was: “Ah, now we can be released into action.” K: Do you call yourselves activists? L: I do sort of wince when people refer to me as an activist – inwardly wince. I can feel my cells tighten up. And I think it’s because it’s a simplistic label. And anything that has an “ism” seems to be over simplified. J: Including Buddhist. L: And I feel the same way if anyone says I’m a Buddhist. Are you a Buddhist? I just want to slap them. No, I don’t want to do that.I feel awkward about it. Claiming it. Is that my identity? Activist, is that my identity? Well the people I think of as activists I’m not sure I want to be classified with them. So maybe I also am labeling people that way. One of my most honored teachers, and I did get to meet him during his lifetime, was Paulo Freire. And he called it mere activism.Because it tends to sort of pick an issue, and not be about consciousness raising or about the whole picture of what’s wrong. He speaks about being active as opposed to being an activist. J: I’m nervous about any labels that let anybody off the hook. My calling is to help people find that the motivation exists within them. The person everyone needs to hear is inside them. I want to help them liberate their own voice so they can hear from themselves what they care about and what they want to do and what they see as possible. And then they become a voice for the earth. A voice for all beings. They discover their bodhisattva nature. I invite them to experience and to get in touch with what they know and feel and see happening to our world – to be in touch with what feels truest about their own deep responses to the conditions of the world and then to see it as beautiful and trustworthy, and worthy of respect as well. L: That’s so beautifully said and also expresses what has been at the center of my work as a writing teacher. In the field of helping people become the writer that they are, you absolutely have to believe that they have it in themselves. There’s no way anybody can put words in someone’s mouth and they become a powerful writer. Their voice just doesn’t come out that way. It only comes out when things are opened up inside and that allows that person to express what they have to express. People want this very much. J: People want to be real, don’t they? L: They want to be real and especially when they feel pain for the earth they want to be able to do something. And that’s very extreme right now. I have been almost overwhelmed at how many people have come to workshops called “Undoing the Silence.” The term really speaks to people because they know that they’ve experienced silencing and that they’re not speaking up. You were asking earlier if we don’t use the word activist, what do we use? I think I use the word “engage”, “involve”, “take action”. J: I use the word “liberated” a lot. Liberated into action. That’s what we most want to do, is to be part of the healing of our world. That’s the deepest desire. K: What is it that causes people to censor themselves? L: Fear, fear and fear! When I realized I had to write a whole chapter on this for my book, I had a lot of fun thinking about what are all the factors in it. People don’t have self esteem. Everything they’ve encountered in society – their parents, their schooling, their teachers, their workplace -the whole culture has reinforced this feeling that you’re nothing. You’re a cog in the wheel. Children should be seen and not heard. It’s dangerous to speak out.A few years ago a Veterans Administration nurse spoke out about the suicide rate of returning veterans from Iraq and was very critical of the army policy about that. She lost her job. But this happens everywhere. Each person has a different story of silencing. J: And that’s embedded by the isolation in which we live.This is a nation of lonely and isolated people. It is a competitive, industrialized consumer culture. You don’t feel you have the support of others in speaking out. L: Yes. And you don’t feel heard. You can’t speak out if you know people aren’t listening to you or are discounting or marginalizing you. It just doesn’t come out right. J: I think it’s fear of pain -of moral pain. Of feeling the suffering of our world. L: One man said that in a workshop I gave in New Orleans about six months after Katrina.We were discussing “what makes us silent.” And he said “I don’t want to write these things that I’ve just learned about our government because I fear that if I really say the truth that it will be too awful even for me to bear. The truth is too awful. It will hurt me.” J: Then there’s the fear that if I say how bad it is, I’ll be stuck in that forever. And I’ve got a life to live and a family to support and I can’t afford to admit how hopeless the situation is. Here the Buddhist teachings are so valuable because they affirm the impermanence of all feelings.They’re just feelings. They come and go, and we’re only stuck with what we’re resisting, what we’re trying to hold at arm’s length – that’s when we’re stuck. But if we speak the fear, speak the grief, speak the outrage, and the emptiness then you’re free from it in a very real way. K: Do either of you still face challenges to speaking and acting? J: Oh, all the time! L: I couldn’t be a teacher ifI weren’t encountering it myself and knew what it felt like. That’s how I became a writing teacher, because Iwas very, very painfully self-critical about my writing and took nine years to write my dissertation. I critiqued every sentence on every page before I went onto the next one. And I suffered greatly. And my ego was very involved in it. And it was just a miserable experience. But when I realized that all my students were suffering even worse from those problems, I learned that there are ways to undo that. Ways to give yourself permission to speak. Make the corrections later, and that kind of thing. But I’m not out of the woods. I still feel it every time I sit down to write something. J: There again, the Buddhist teachings of the self are so invaluable. Because our feelings of futility, of self castigation, of overwhelm, of cynicism- I just remind myself: these are just feelings. If I can remember. That’s why the meditation practice is so helpful. You train. Particularly I’m grateful to vipassana because you train the mind to look at the mind and see the rising and falling of these dharmas of feeling and sensation and you don’t take them seriously. They’re part of the stream. It’s just invaluable. So then, you make a mistake, for example. So what? You know self importance always will come up – the self importance of not being perfect enough or not being eloquent enough or missing the mark. But it really helps to not take yourself too seriously. And there again, particularly from my experience, vipassana helps you take things lightly and to see yourself as this flow or stream of being, – bhavangha. K: Do you have any thoughts on the role of Spirit Rock and other Buddhist retreat centers in helping address issues like the current climate crisis? Does it make sense for retreat centers to stay out of politics or should they be more to be involved?” L:I don’t think anybody can stay out of an issue like climate change. After all, if this is a world where everything is interconnected, then we’re part of it.In the tradition I mostly practice in, Thich Nhat Hanh’s Plum Village system, they’ve taken to having car free days at the monastery in Escondido, Deer Park monastery. Now, what could a practice center like Spirit Rockdo – and I don’t know what actions it has taken – but there are all kinds of levels, whether it’s having an occasional retreat on the subject, or working on recycling, or further. I love the idea of practicingin a place that’s working to be as little a part of the problem as possible and be raising consciousness about all of the problems. Not just climate change but racism and poverty – all of those issues. J: The Buddha often said that his teachings were to help people live without causing more suffering to themselves, and their brother-sister beings. And I think that’s a good aspiration for a retreat center. K: Were there any moments in your life that stand out as a kind of fork in the road between living a more ordinary life vs. choosing a life dedicated to service and the planet and all that? J:For me it would have to be countless moments like that. It’s almost a kind of daily dedication. And I suppose there have been in my life mountaintop experiences where I felt really called,and they’re important. But also important is just getting out of bed in the morning and deciding that this day is precious and sacred and that you’re going to live it that way. L: There have been many times for me too when I was just was filled with tears and a sense of the enormity of the issues. And maybe that’s the moment of dedication.But I know I could never find one watershed moment. J:The opportunity to feel called to give yourself arises all the time, it seems to me. And with each, the sense comes, “Oh how fortunate I am to live in a time of the great turning where we can hear about the needs. Where we can know them and play a role.”We’re very lucky. It’s a great privilege to be alive at a time when we can be of use. Because I think this being of use is intrinsic to life. |

© Kerry Nelson